Modern test automation often starts with simple scripts — a few clicks, a login, a form submission. But as projects grow, these tests can become fragile, repetitive, and hard to maintain. The Page Object Model (POM) has been the standard way to structure E2E UI tests for years, but it has limitations, especially in large-scale or multi-surface testing.

The Screenplay Pattern takes a different approach. It models tests around user behavior rather than application structure, making them more modular, readable, and scalable. In this article, we’ll explore what the Screenplay Pattern is, when to use it, and how we implemented it using Playwright.

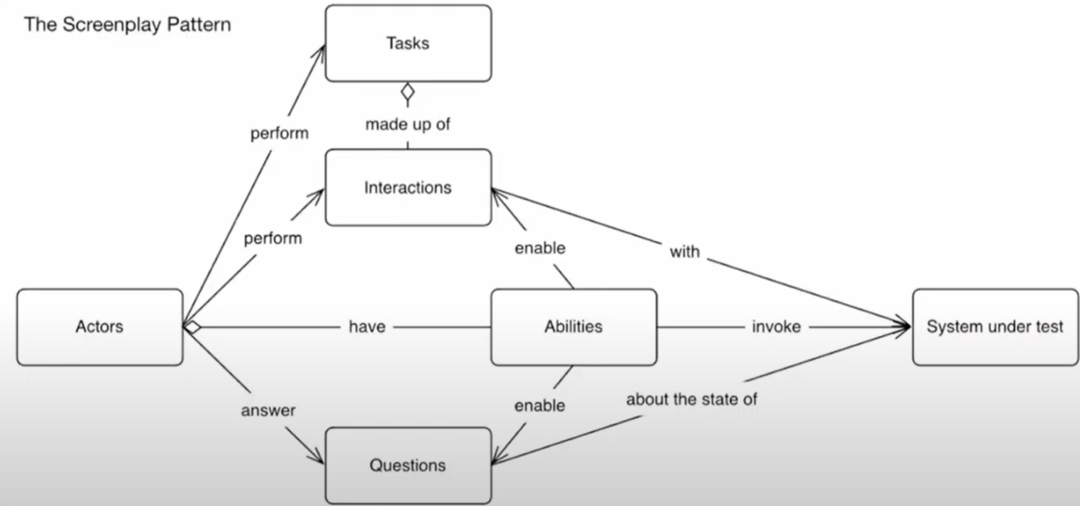

The Screenplay Pattern at a Glance

Here you can see the high-level flow:

- Actors – The personas in your test, such as “Admin”, “User”, “Guest”, etc.

- Abilities – What those actors can do (e.g., browse the web, call APIs, query a database, interact with a Cloud Service).

- Tasks – Represents what the actor wants to do in a business sense (e.g., log in, update a profile, perform a search in a table with data).

- Interactions – The smallest units of behavior (e.g., click a button, fill an input, press keyboards).

- Questions – A query made by the actor to verify something in the system (is the skill visible? did the API return the correct payload?).

Actors use their abilities to perform tasks made up of interactions, and they ask questions to validate outcomes.

Why Move from POM to Screenplay?

The Page Object Model works well for web UI-only automation. If your testing scope is limited to browser-based E2E testing, POM can still be the right choice. But our automation needs went far beyond that — covering not only the web interface, but also APIs, database validations, and potential integrations with cloud services.

Here’s where Screenplay shines:

- It’s technology-agnostic — you can automate anything (Web, API, DB, Cloud) simply by creating a new Ability for the Actor.

- It standardizes design across teams. Without a shared pattern, we’ve seen engineers implement wildly different styles for APIs, DB clients, or cloud SDKs — often with painful maintenance consequences.

| Feature | Page Object Model | Screenplay Pattern |

| Abstraction | Models UI structure (pages) | Models user behavior (intent) |

| Reusability | Moderate | High (Tasks and Questions are composable) |

| Test Readability | Functional steps per page | Narrative, actor-driven |

| Maintenance | Centralized per page | Centralized per business behavior |

| Scalability | Limited with many components | Designed for scalability |

| Learning Curve | Low to medium | Medium to high (but pays off in large projects) |

| Design Speed | High | Medium |

Applying Screenplay with Playwright

In our implementation, we modeled the following:

- Actor Example:

const Alice = Actor.named('Alice')

.can(BrowseTheWeb.with(page))

.can(CallTheAPI.using(apiClient));

- Ability Example:

class BrowseTheWeb {

static with(page) {

return new BrowseTheWeb(page);

}

page() { return this.pageInstance; }

}

- Task Example:

export const FilterTable = {

by: (filterValue) => Task.where(`#actor filters the table by "${filterValue}"`,

Click.on(TablePage.filterDropdown),

Select.option(filterValue).from(TablePage.filterDropdown)

)

};

- Question Example:

export const RowShouldBeVisible = (rowText) =>

Question.about(`the visibility of a row containing "${rowText}"`, async (actor) => {

const page = actor.abilityTo(BrowseTheWeb).page();

return await page.isVisible(`table tr:has-text("${rowText}")`);

});

});

When to Use the Screenplay Pattern

Screenplay excels in:

- Large, evolving systems with multiple interfaces (UI, APIs, databases, cloud).

- Scalable teams where shared patterns prevent code divergence.

- Cross-functional testing that combines UI actions with backend verifications.

When Not to Use It

Screenplay might be overkill for:

- Small projects with limited scope.

- UI-only testing where POM is simpler and sufficient.

Teams with no prior functional programming experience — Screenplay benefits from familiarity with concepts like functional interfaces, streams, and lambdas.

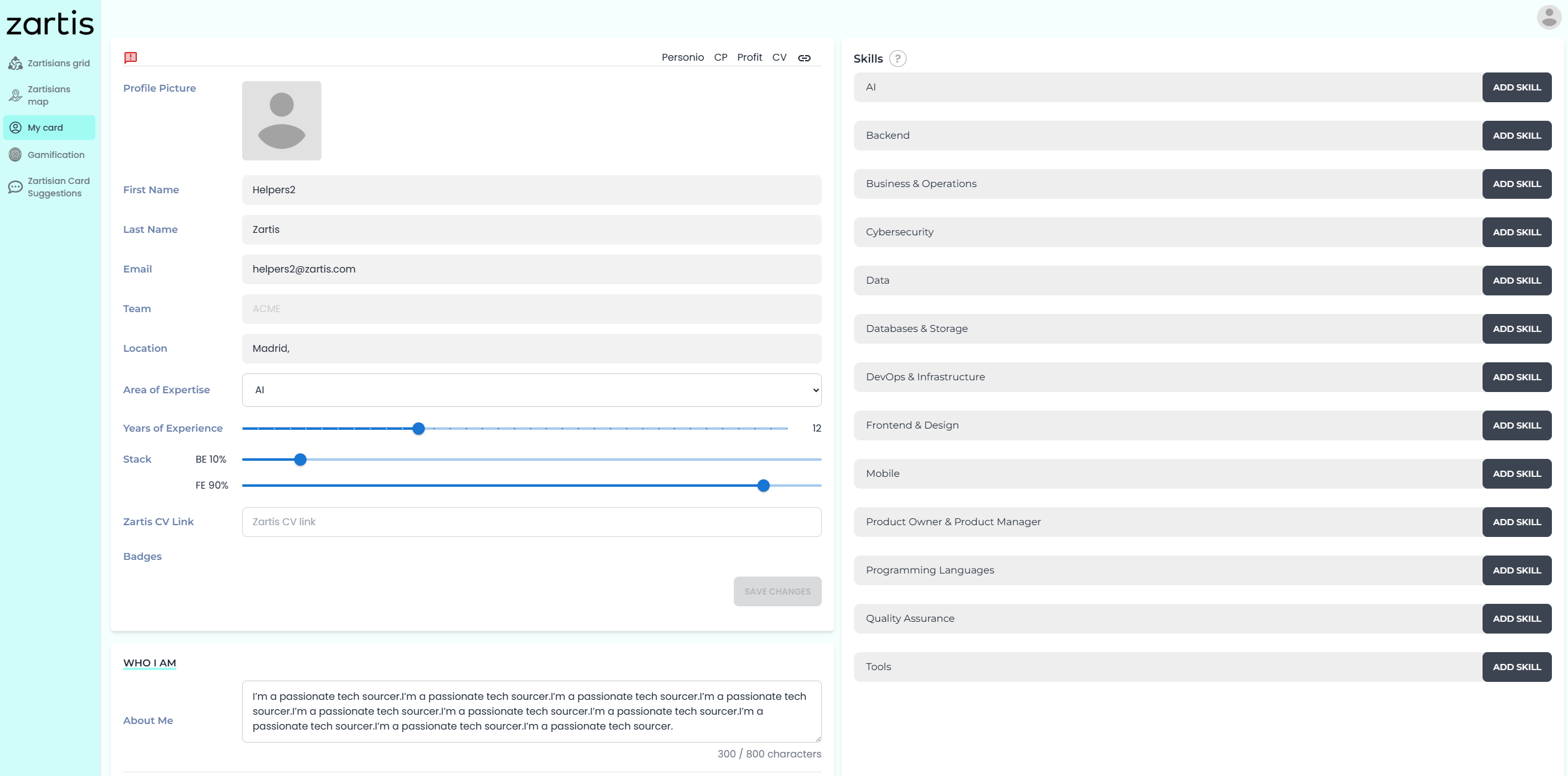

Case Study: Screenplay in Zartis Card

Zartis Card is an internal application that serves as the company’s technical database. It provides an overview of employees (“Zartisians”), including their location, expertise, and key professional details.

One of its core features is the My Card section — a personal profile where Zartisians can review and update their skills, proficiency levels, and years of experience. This functionality supports important use cases like internal project staffing, cross-team collaboration, and expertise tracking.

For our end-to-end testing, the “add skill” flow in this section offered a perfect example to apply the Screenplay Pattern. The process requires a sequence of distinct UI actions — selecting a skill category, picking a skill, specifying years of experience, choosing a proficiency level, and saving changes — followed by a validation step to confirm the skill appears in the profile.

Project Folder Structure

The Zartis Card automation tests are organised to reflect the Screenplay Pattern’s core building blocks — Actors, Abilities, Tasks, Interactions, and Questions — with each feature split into its own domain folder.

tests/

actors/

zartisian.ts

features/

auth/

auth.json

authSetup.spec.ts

profile/

interactions/

clickAddSkillButton.ts

clickSaveSkill.ts

fillYearsOfExperience.ts

selectSkill.ts

selectStarRating.ts

questions/

isNewSkillAddedToProfile.ts

isProfilePageAccessible.ts

tasks/

addSkillToProfile.ts

navigateToProfileFromSidebar.ts

profile.spec.ts

support/

screenplay/

abilities/

navigate.ts

base/

baseActor.ts

interfaces/

ability.ts

interaction.ts

question.ts

task.ts

Actor Example – Zartisian

The Zartisian class extends BaseActor, providing a domain-specific name for the actor and wiring in the Abilities they need for a given scenario.

In our Zartis Card tests, the Zartisian actor is a concrete implementation of an abstract BaseActor class:

typescript

CopyEdit

// baseActor.ts

import { Page, Locator } from "@playwright/test";

import { Task } from "../interfaces/task";

import { Question } from "../interfaces/question";

import { Ability } from "../interfaces/ability";

/**

* Base class for all Screenplay actors.

* Encapsulates the Playwright `Page` and shared methods.

*/

export abstract class BaseActor {

constructor(protected readonly page: Page) {}

private readonly abilities = new Map<new (...args: unknown[]) => Ability, Ability>();

async attemptsTo(...tasks: Task[]): Promise<void> {

for (const task of tasks) {

await task.performAs(this);

}

}

async asks<T>(question: Question<T>): Promise<T> {

return await question.answeredBy(this);

}

can<T extends Ability>(ability: T): void {

this.abilities.set(ability.constructor as new (...args: unknown[]) => T, ability);

}

abilityTo<T extends Ability>(abilityType: new (...args: any[]) => T): T {

const ability = this.abilities.get(abilityType);

if (!ability) {

throw new Error(`Actor does not have ability: ${abilityType.name}`);

}

return ability as T;

}

getPage(): Page {

return this.page;

}

getLocator(selector: string): Locator {

return this.page.locator(selector);

}

}

Task Example – AddSkillToProfile

A Task represents a business goal from the actor’s perspective. In Zartis Card, adding a new skill to a profile involves several distinct UI interactions — selecting a category, picking a skill, specifying years of experience, choosing a proficiency level, and saving.

import { Task } from "../../../support/screenplay/interfaces/task";

import { Zartisian } from "../../../actors/zartisian";

import { ClickAddSkillButton } from "../interactions/clickAddSkillButton";

import { SelectSkill } from "../interactions/selectSkill";

import { FillYearsOfExperience } from "../interactions/fillYearsOfExperience";

import { SelectStarRating } from "../interactions/selectStarRating";

import { ClickSaveSkill } from "../interactions/clickSaveSkill";

export class AddSkillToProfile implements Task {

constructor(

private readonly params: {

category: string;

skillName: string;

years: string;

levelTitle: "Learn" | "Use" | "Use +" | "Teach" | "Teach +" | "Master";

}

) {}

async performAs(actor: Zartisian): Promise<void> {

const { category, skillName, years, levelTitle } = this.params;

await actor.attemptsTo(

ClickAddSkillButton.forCategory(category),

SelectSkill.called(skillName),

FillYearsOfExperience.withValue(years),

SelectStarRating.as(levelTitle),

ClickSaveSkill.forCategory(category)

);

}

}

Question Example – IsNewSkillAddedToProfile

A Question in the Screenplay Pattern represents a query the actor makes to verify the state of the system under test. In this case, after adding a new skill, the actor checks if that skill appears in the profile’s skills list.

import { Question } from "../../../support/screenplay/interfaces/question";

import { Zartisian } from "../../../actors/zartisian";

export class IsNewSkillAddedToProfile implements Question<boolean> {

private constructor(private readonly skillName: string) {}

async answeredBy(actor: Zartisian): Promise<boolean> {

const page = actor.getPage();

// Small wait to ensure UI updates before querying

await page.waitForTimeout(1000);

// Locate the selected skill in the dropdown

const selectedOptions = page

.locator('[data-test="skills-dropdown"]')

.locator("option:checked");

if ((await selectedOptions.count()) === 0) {

return false;

}

const visibleText = await selectedOptions.textContent();

return visibleText?.toLowerCase().includes(this.skillName.toLowerCase()) ?? false;

}

static called(skillName: string) {

return new IsNewSkillAddedToProfile(skillName);

}

}

Test Example – end-to-end flow

This test demonstrates the full chain — Actor → Task → Question — in the context of adding a new skill to a profile.

import { test, expect } from "@playwright/test";

import { Zartisian } from "../../actors/zartisian";

import { NavigateToProfileFromSidebar } from "../../features/profile/tasks/navigateToProfileFromSidebar";

import { AddSkillToProfile } from "../../features/profile/tasks/addSkillToProfile";

import { IsNewSkillAddedToProfile } from "../../features/profile/questions/isNewSkillAddedToProfile";

test('@smoke Zartisian can add a new skill in profile page', async ({ page }) => {

const zartisian = new Zartisian(page);

const skillName = "Chatbots";

// Navigate to profile page

await zartisian.attemptsTo(new NavigateToProfileFromSidebar());

// Check if the skill already exists

const alreadyAdded = await zartisian.asks(

IsNewSkillAddedToProfile.called(skillName)

);

if (alreadyAdded) {

console.warn(`Skill "${skillName}" is already in the profile, skipping test.`);

return test.skip();

}

// Add the skill

await zartisian.attemptsTo(

new AddSkillToProfile({

category: "AI",

skillName: skillName,

years: "1",

levelTitle: "Use",

})

);

// Verify the skill is now visible in the profile

expect(

await zartisian.asks(IsNewSkillAddedToProfile.called(skillName))

).toBe(true);

});

Key Takeaways

Adopting the Screenplay Pattern in Zartis Card brought clear benefits:

- Maintainability – UI changes require updates only to small, isolated Interactions.

- Readability – Test scenarios closely match business language, making them easier to understand.

- Reusability – Tasks and Abilities can be composed in different ways across test flows.

- Scalability – Works equally well for UI, API, and cloud service testing.

That said, the transition came with challenges. It requires discipline to avoid over-engineering and to ensure the structure remains consistent across contributors.

From this experience, a few lessons stand out:

- Start with a small pilot feature to get the team comfortable before wider adoption.

- Avoid introducing BDD frameworks unless the team understands declarative vs imperative styles.

- Invest in onboarding documentation to explain Actors, Abilities, Tasks, Interactions, and Questions.

- Keep Tasks small and focused so they represent a single business goal.

Final Thoughts

The Screenplay Pattern represents the next level of sophistication in automated testing. While POM has served us well, Screenplay allows us to scale tests with better structure, richer expression, and domain-oriented modeling.

It encourages clean architecture and makes the intent behind each test clearer for both developers and business stakeholders. The transition requires some investment in setup and learning, but the payoff is long-term gains in clarity, maintainability, and robustness — especially in projects with broad feature sets or complex user journeys.

If you’re facing brittle tests, inconsistent code across teams, or want a framework-agnostic approach that works across UI, API, and cloud testing, give Screenplay a try. Start small, share successes, and you’ll quickly see why it’s worth the shift.

Author: